Ex Himalayan Venture 18, the principal expedition of RAF100, was an exploratory expedition to the Rolwaling and Khumbu regions of the Nepalese Himalayan range. Team 03, the team of University Air Squadron Officer Cadets were on expedition from 28th August to 21st September whilst Team 04, the team including the RAFAC contingent, were on expedition from 29th August to 22nd September 2018. HV18 was a celebratory expedition in honour of the centenary of the RAF, the 75th anniversary of the RAF Mountaineering Service and the 70th anniversary of the RAF Mountaineering Association.

Led by RAF Mountaineering Association, HV18 was the largest RAF expedition in history, with a total of 75 personnel deploying to Nepal. The expedition was designed around three aims: Unite, Develop, Pioneer. To unite individuals across the RAF family; to develop the skills, robustness and expeditionary spirit of all applicants; and to pioneer new routes and experiences in Nepal. In the spirit of such a celebration, the whole RAF family was involved – Regulars, Reserves, UAS Officer Cadets, RAF Air Cadets and Veterans.

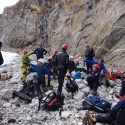

HV18 was compiled of five teams: one alpine climbing team and four trekking teams. The alpine climbing team were successful in achieving their aim of leading the first British ascent of Mt Langdung (6357m). The four trekking teams each had a unique itinerary, completing remote routes in the Khumbu and Rolwaling valleys. Team 03 and 04 followed the same route, merely one day apart. Unlike Team 03 which was solely made up of UAS officer Cadets, Team 04 was mixture of regulars, reserves and RAF Air Cadets, the team was an incredibly diverse group, each person with a very different background and experiences. The route spanned in excess of 200km with an overall height gain greater than Mt Everest (8848m). Starting at Jiri, the teams explored rarely visited villages and mountain passes along the original 1953 Everest Expedition route; even camping near an original 1953 campsite, before branching off west to the Tesi Lapsa Pass and to the Rolwaling Valley beyond.

Crossing the Tesi Lapsa Pass (5755m) was an ambitious objective. A three week long trek, slowly climbing towards the Tesi Lapsa Pass provided acclimatisation for all 15 members of each team to summit on the 15th September, at 0840hrs and 16th September, at 0745hrs respectively.

HV18 was more than a trekking expedition. It was an 18 month long journey, that saw applicants gain new qualifications and unite with other members of the RAF family. Even whilst on expedition it was not merely a trek. All members participated in or assisted with a MOD research project investigating performance and health at altitude. Furthermore, expedition members supported the UK and RAF100 Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) efforts with active demonstrations of practical applications and importance of STEM. Time was taken on the trail to take part in the Royal British Legion Every One Remembered campaign. In addition, the team interacted with local communities along their route and took the time to embrace and understand local culture.

Involvement in the planning and delivery of the expedition

The training programme for HV18 spanned 18 months. Whilst some amendments to the training programme were made minimise the impact of school or university absences, the UAS Officer Cadets and RAF Air Cadets complied with the same selection criteria as all other members of the expedition. All participants undertook the Summer Mountain Foundation and Winter Mountain Foundation courses, in addition to numerous other training weekends and other mandatory events.

The Cadets integrated themselves with the RAF Regular and Reserve members of expedition, particularly those in Team 04, on each and every training event, and this ensured that the team quickly coalesced. During this time, the Cadets’ enthusiasm for adventure training (AT) grew, and each of the Cadets now has a personal objective to work towards and achieve AT qualifications, such as the Mountain Leader Summer Award. Throughout the 18 month process, the cadets have been keen to further their knowledge and experience.

In Team 04, the test of the Cadets development came during the expedition, with each Cadet using their initiative to develop their mountaineering skills, specifically route planning and navigation. The Cadets achieved this by taking turns each evening to work with Team 04 Technical Safety Officer to plan the route for the following day. They would then brief the whole team after dinner before turning in, so that everyone was fully informed about the next stage of the journey. Their briefings were detailed, highlighted any significant challenges and points of interest, the days timings and specific kit requirements, and lastly points of safety.

The following day, supported by the Sherpa team, the Cadet who briefed the team the previous evening took the lead in navigation. By doing this each day, the Cadets improved their navigation skills, and furthermore, their confidence at team leadership developed. Whilst initially slightly apprehensive about briefing regular and reserve RAF personnel, they grew into the role and provided an excellent brief. While working with the embedded Sherpa team in such close fashion, the Cadets developed their communication skills and understanding of the cultural differences which they said enriched their overall experience of HV18.

The teams were also involved in testing satellite communications equipment for Inmarsat, a communication company based in London. The sat-phones were tested each day in order to assess performance and reliability and were used in a range of locations and climatic conditions throughout the expedition. One of the tasks the Cadets chose to be involved with was providing a situation report (sitrep) to HV18 Base Camp. Each evening, the Cadets wrote a sitrep about the day to update the higher planning committee on the progress and wellbeing of Team 04 as a whole. Their sitreps were reviewed by Team 04 Expedition Leader, then sent to HV18 base camp. Using satellite communication was a unique experience for the Cadets, as satellite communication is not regularly used during RAFAC expeditions.

The development of cultural understanding amongst participants

Nepal is a country rich with culture and you cannot walk 100 metres without seeing prayer flags and Buddhist symbols and calligraphy. The Sherpa teams were excellent educators and welcomed our questions as we looked to learn more about our host country. In Buddhist culture, it is considered good luck, to walk in a clockwise direction shrines and Mani stones and to spin prayer wheels in the same clockwise direction. It wasn’t long before the team started subconsciously diverting off the path to ensure they passed on the left hand side.

An additional objective of HV18 was to participate in the Royal British Legion’s (RBL) #ThankYou100 campaign. To achieve this, each member of Team 04 selected a person from World War One to remember during the expedition. Their photo was printed out, laminated and a short description of who they were was written on the back. As the principal photographer, Cadet Flight Sergeant Entwisle organised a series of video messages, filmed at a local Nepalese school, in which each member of Team 04 explained who they were remembering. Cadet Sergeant Lewis Scott took a special interest in this and chose to remember his great great uncle. His family did not previously have any information on their lost family member, it was through his dedicated research that he found out a whole history of him and even managed to find a photo! Without exception, the whole of Team 04 and the Sherpas found this and extremely moving and emotional experience.

The teams were supported by an excellent team of Sherpas and porters. The RAFAC wanted to include them in our #ThankYou100 contribution so the Cadets explained to the Sherpas and porters who the RBL are and the significance of the #ThankYou100 campaign. Individuals volunteered to have their photo taken with a selection of the remembrance photos, and there was a whole team photo with the RBL flag we were carrying. By including the Sherpas and Porters in our remembrance service, our two cultures were genuinely brought unexpectedly closer together. It was particularly poignant given when in Kathmandu we had visited the Military hospital which has a Great War Memorial on the front of the building.

Involvement with local communities

During HV18, the RAFAC were privileged to meet a wide variety of Nepalese communities, in both populated and extremely remote regions of the country. The Sherpa and porter communities worked very closely together, and we built a strong rapport with our Sherpa and porter team. Nepal is a very poor country, however, the whole team was struck by peoples’ warmth and hospitality. In the trekking industry, being able to speak English significantly improved the chances of people having better paid jobs. The RAFAC discovered this during their expedition research before we left, therefore, decided that they would teach our porters English as they are often not given an opportunity to learn.

An unforeseen advantage of this daily move of the expedition toward its objective, was the captive classroom of the dedicated team of Porters and Sherpas in our peripatetic school!

During the trip, either while trekking or in the evenings at campsites, the Cadets spent time teaching the Porters to speak and improve their English. Their lessons were based on conversation, focusing on phrases that would be beneficial to the porters on future expeditions. While conducting these lessons, the Cadets discovered that many of the porters were of a similar age: 17-20: this fact made quite an impact on the Cadets as each porter would carry bags of up to 45kg along each and every step that Team 04 took, all tied together with rope and strapped and suspended from their heads. During the latter part of the expedition the Porters allowed the members of Team 04 to have a go at lifting and carrying the daily burden, providing great amusement to everyone! At the end of the expedition, the porters huge efforts were acknowledged and they were gratefully tipped; the Cadets wanted to tip the porters who were the same age as them, personally as a thank you.

As the expedition drew to a close the Cadets became aware that the porters were spending the evenings playing a game. The game involved flicking a counter into a coloured counter with the aim or sinking that coloured counter in a hole in the corner of the playing surface. There were significant similarities with this game and pool or snooker.

The Cadets asked questions and learnt the rules and were invited to play with the porters. This culminated in an end of expedition match with a Cadet and Porter being paired to play against another Cadet and Porter duo. The game meant for a few hours the language barrier, cultural difference and time was forgotten. The Cadets and Porters thoroughly enjoyed the game and it was a brilliant spectator sport as locals gathered to watch the spectacle.

Notable physical challenges and achievements

Aside from the necessarily lengthy duration, the most notable physical challenge of the expedition was summiting Tesi Lapsa Pass (5755m). This is one of the highest RAFAC expeditions to have taken place, and when height and Latitude, duration and weather is taken into consideration, it is considered ‘The Most Difficult Trek in Nepal’. The length of time at altitude was extensive to ensure a safe and thorough acclimitisation profile; twenty days were spent from starting the trek till the final checkpoint. As previously stated, the combined overall height gain was far greater than Mt Everest (8848m) and the distance trekked far greater than 200km. A long and progressive period of time at altitude ensured each member of the team was fully acclimatised for the summit ascent, after withstanding the inevitable effect of grinding down the energy and resolve of human spirit.

On the day we summited Tesi Lapsa Pass, Team 04 woke early at 02:30 – a true ‘alpine start’. After forcing down a necessary bowl of porridge and sipping black tea, the team started trekking at 03:15. The morning was dark, and cold at -10 degrees, yet the night sky was extremely clear. Light from stars and head torches touches the mountain cliffs and glaciers that were on either side of our route. The effects of altitude meant that the team could only take two or three paces before needing to stop to catch our breath. The Cadets reflected that this part of summit day was the most challenging, yet each of them demonstrated great determination and resilience. Gradually, the sun rose and our route could be seen more clearly, which may not have lifted spirits! Heading closer to the summit, the teams put their helmets on in preparation for using fixed ropes to traverse some steep, rocky terrain. Huge physical and psychological effort was needed to concentrate on balancing strength and coordination needed to continue moving up the mountain side, without over exerting and needing to stop to recover from the lack of oxygen.

The Cadets were seen as equals among Team 04, checking on other members and giving encouragement.

Eventually, with perseverance and a great sense of relief, Team 04 summited Tesi Lapsa (5755m), with everyone congratulating each other on the achievement and experience the elation and emotion of the effort. The team gathered for a summit photo, and after attaching some prayer flags to the col, we started the descent over the other side of the mountain pass to Glacier Camp.

The adventurous nature of the expedition

This was the RAF’s largest ever mountaineering expedition. To involve the whole of the RAF Family was unprecedented.

The sheer challenge of the expedition meant that there were many unknowns, such as weather conditions or accessibility of routes: none of HV18 was in any way certain. Once the team had successfully summited Tesi Lapsa Pass, it entered the Rolwaling Valley, a very rarely visited area of Nepal, especially at this time of year, while the Monsoon was still to finish. The Rolwaling Valley is very, very remote indeed, and in fact on arriving at one village we planned to break at, no one was there! Even the local people had not arrived back from their winter homes further down the valley. The amount of unknowns that the participants experienced during the expedition ensured the expedition had an adventurous undertone all the way from Kathmandu and back again.

Unique aspects of the venture

A unique opportunity that all expedition members were involved with during HV18 was contributing to medical research. The MOD funded a project that investigated the effects of beetroot supplements on performance at altitude. Beetroot contains a high concentration of nitrates which is a mineral needed for cardiac function. The MOD funded this project to establish if taking beetroot supplements at short notice improved cardiac and physical performance at altitude. When troops were deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq, they started to operate at 3000m without any acclimatisation period. Unsurprisingly, many troops became ill with acute mountain sickness (AMS) very quickly. AMS is a serious condition that can lead to fluid retention in the lungs or cerebral swelling. The hypothesis of the study was taking beetroot supplements two days before and during the expedition would increase performance at altitude. A placebo was given to half of the group as a control measure to establish if the nitrates present in beetroot had a positive effect on acclimatisation.

There were many volunteers from both teams that opted to be research participants in the study. Many chose to do this because they would either like to pursue a military career once they have finished studying or because they saw the impact on future mountaineers that this research may have. Those unable to take part in the research, contributed to the study by helping with the research admin. This involved organising the research participants’ workbooks twice a day and helping with collecting vital signs observations such as blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturations.

Participant Reports

The Journey of a Lifetime for the Trip of a Lifetime

By Cadet Flight Sergeant Jonny Heaton

The journey for the Air Cadet Team began in Scotland. We had sent and received many emails, spoken on the phone to Air Cadet staff and questioned what we had signed up for, but stepping out on the firm crisp snow on Cairn Gorm with the HV18 expedition leader will stick in my mind. Whilst focussing on my feet as I practised the appropriate techniques for walking on snow and ice and ensuring that my crampons did not attack my trousers, I could hear the HV18 expedition leader excitedly explain how awesome this expedition was going to be.

Much training and many months later, we arrived at Heathrow – the starting point for our mammoth adventure. Due to operational commitments amongst the Regulars, this was the first time that all fifteen members of our team had been together. We had all met on a few occasions but this was the first time that we united – I would never have expected us to become the tight knit and cohesive group that we became as a result of our adventure.

It was only whilst standing waiting to check in, that the reality of what we faced dawned on me. There was a sea of red t-shirts as we all queued in our matching branded t-shirts. Airport trolleys overflowed with duffel bags and rucksacks – there was personal kit, group kit, medical research kit – all carefully sorted and packaged for departure. The team stood in line making small talk, pondering on what would be to come.

After a few days in Kathmandu – sightseeing, packing and repacking kit and making our final preparations. The journey to our starting point at Jiri was more of an adventure than I had anticipated. I thought that the adventure would just be whilst trekking not on the bus ride.

The journey started off as a planned, 7 hours ticked by, each time we looked out the window we were greeted by another vista. The views were impressive, in the distance we could see large mountains towering up for the horizon – we were heading towards them. We were frequently told by our Sardar and the bus drive that we were “Only 2 hours away”; this continued until we had been traveling for over 10 hours. Without any warning the trees broke from the sides of the road and we pulled into a small market town – we had arrived.

But we weren’t stopping, we decided that in an effort to spend an additional day at high altitude acclimatising, we should push on in the bus to get a day ahead of schedule. For me, this set the tone for the team for the whole expedition, nobody had enjoyed the previous 10 hours but we all wanted to get a day ahead so that we could spend more time at altitude and ultimately have a better chance at reaching the Tesi Lapsa.

The final leg of the bus route from Jiri, where the bus repeatedly got stuck, we were tossed from side to side, and bags slide down the aisle, will stick with me forever. With the monsoon still in full force, a recent mudslide has made the road – if you can call it that – more treacherous than normal. At some points, we daren’t to have looked out the windows, due to the steep drop down the mountain millimetres from the edge of the tyre.

The remarkable moment was when, the drivers assistant, jumped from the bus, whilst it was still moving, through deep rutted mud tracks to assist with getting the vehicle unstuck. Running through the mud with flip flops was achievement enough but having got the bus moving, he launched himself back on the bus. To our amazement, his legs, feet and flip flops were clean of mud.

Sat in awe gazing up at the Himalaya

By Cadet Sergeant Lewis Scott

We had arrived at Thengpa. It was cold, wet and not very pleasant. In typical Team 04 fashion, we were in the cloud and there was very little to see. Over the course of the expedition, we had been accustomed to walking and living in a cloud. Despite the lack of views, spirits were high, we knew we were now only days away from the Tesi Lapsa Pass and we were progressing nicely.

In this small mountain village, we met a small boy named Tenzing. We lived with his parents in a tea house that we dined in and set up camp effectively in their back garden. The young boy who had the biggest most infectious smile, had a reasonable understanding of English. We played football with him on the grassy hills behind his house – a note for next time, football is hard tiring work at over 4000m! we sat with him in the evening and asked him about his life and where he went to school. We were amazed to hear that his school was in the next village, it took us 4-5 hours to walk there!

It grew dark and we retired to our tents, whilst we were still in thick cloud, we thought we could see some stars twinkling above us but perhaps that was just my exhausted imagination. At just gone 5am, I stirred in my tent, it was getting light outside. Staying in the warm comfort of my sleeping bag, I unzipped my tent and peered out to see if anyone else was awake yet. I could not believe what I saw before me.

We had camped in front of a towering wall of rock, capped with snow and ice. A huge snowy 6000m peak dominated the landscape as the sun slow rose and illuminated the valley. It was in this moment that the size and scale of the expedition was put into perspective, we were not walking in small mountains like we have at home, I felt we were in a whole new world. Words fail to describe the sheer size and power of the breath taking peaks on each side of the valley that morning. It is a sight, that I am sure will be forever, ingrained in my memory.

The longest day of my life – Summit day

By Cadet Flight Sergeant Chris Entwisle

As though from a nightmare, I was awoken by Cshirring unzipping my tent with bowls of porridge being thrust towards me. A 0230 wake up is not okay in any teenagers books. After quickly getting changed ahead of the big day I bolted down the rapidly cooling bowl of slow release energy only to be greeted by the rest of the team, each just as bleary eyed as the other. What confuses me most, and will continue to for the rest of my life is the energy and willingness of the porters at 3am at 5100m perfectly matched that of them at 4pm at 2000m – leaving us British appearing as mere mortals in awe of their ability at altitude.

To the ordinary onlooker, 15 head torches bobbing up a mountain in the falling snow, at -10°C, before dawn would sound like insanity. And in retrospect it probably was, if not for the risk of mass movement after the ice starts to melt in the sunlight. Without question it was the most quiet and remote place I have ever been; the noise was limited to the tired trudge of B3 mountain boots on the rocky terrain and laboured breathing, interrupted by the occasional cry of “watch out below” followed by rocks clattering. It’s not that the morale was low – the usual chatting and laughter had just become a waste of precious oxygen and a secondary requirement to gasping in what little of it we could afford.

We never saw the sun rise that day. It just sort of appeared, and the cloud we were in at the time of it simply became visible and the need for torches was lost. We all followed in the footsteps of the porters right up to the first bit of rope work where their tracks got lost in the shelter of the overhang. Past the rope we quickly picked back up on their trail, fixed crampons and with the end in sight, pursued their trail eager to summit the Tesi Lapsa. After the longest 500m of my life we reached the high point at 0745: the beast had been tamed.

We forgot all about our shortness of breath. We forgot all about the pain in our feet. Tiredness was all but a distant memory. We were there. Hugs were being thrown around and pictures taken and everyone huddled around Bob’s camera. Morale skyrocketed.

The descent was gruelling on glacial moraine. Rocks were slippery and the sound of rockfall from above was all too common. The return to camp was to be long and gruelling, but the hard bit was done right?

Wrong. The descent involved almost as much up as it did down with the undulating glacier blocking any views of camp. We climbed up slippery rocks only to go back down them, some so steep, that a rope was provided to ensure a safe abseiled descent – we were constantly reminded that this was proper mountaineering and was indeed great fun dropping five meters down an 80° slope on a frozen rope next to the loudest and largest waterfall I have ever encountered with camp in sight.

Without question this was the best day of my life – as well as being the longest.

Keeping up with the Porters

By Cadet Warrant Officer James Clack

Our goal had been reached, the Tesi Lapsa had been crossed on the previous day and we had descended from the dizzying heights of 5755m down to Glacier Camp at 4800m. Yesterday had been a long day but we were well rested. We were now ready for the descent off of the glacier and deeper into the Rolwaling Valley. We were assured by John that it was all down from here – we were pleased. When he said this he meant Himalayan down, which to you and I means there will be plenty of up as well!

The glacial moraine was an unforgiving beast. The end of the glacier was insight, however to get there we need to navigate over, through and around the moraine. It was hard work, every climb up a ridge of rock felt like it should be our last, we spent hours progressing through the moraine seemingly making very little progress. It was frustrating work, but slowly and surely we got closer to the lake marking the end of the torturous terrain.

With the moraine cleared, we progressed down the side of the valley parallel to the glacial lake. Whilst on previous days, we had the summit to motivate us, now we felt we were walking with very little purpose. Morale dropped across the team, music broke out and we had to put up with George’s awful dancing – I’m not sure what was worse his dancing or the glacial moraine.

As the valley arched round to our left, we reached the end of the lake, we could see for miles. Most importantly we could see Na in the distance further down the Valley. Na was our camp for the night. A 100km descent and then 3km along the flat would see us to tea, biscuits but most importantly to rest.

As we progressed down the path, we were passed by some of our porters. Some of which were younger us. They raced past us with 45kg packs on their back and flew down the hill. Amazed by their speed, we asked Nima, one of our Sherpas, if we could go at their pace to Na. Nima stepped aside and said one word, “go!” – we were off chasing down the hill after them. As we got close, Nima shouted something in Nepali and the porters picked up the pace and started running. We kept up with them for a while, but they were too quick. We were sweating, panting and simply couldn’t keep up with them – we were at over 4000m after all!

My Journey

By Officer Cadet Emily Brittain

The application process opened in 2016 with 250+ initial applicants for 5 teams. There was no requirement for previous experience – anyone from absolute novice to experienced mountaineer was invited to apply. I was one of approximately 40 UAS students who expressed an interest to their GTIs with a written application over a year ago. Since then, we have undergone summer and winter training in Wales, the Lake District and the Scottish Cairngorms which whittled us down to a team of 12, plus reserves, mainly based on our personal qualities such as resilience, teamwork and sense of humour! Selection was very tough at times, especially learning winter skills and traversing down icy slopes on crampons, which most of us were trying for the first time! But we all thoroughly enjoyed ourselves and gained qualifications which will benefit ourselves and our squadrons in the future. Through these skill sessions and pre-deployment training we had definitely bonded with a team and become good friends. We travelled to Kathmandu at the end of August, where we had a couple of days to explore and stock up on Mars bars and cheap mountaineering equipment. We also visited the commonwealth cemetery where we shared memories of the fallen mountaineers in the Everest base camp earthquake in 1987 and all those involved in RAFMA today and the past 75 years. This was thought provoking and gave our future endeavours perspective.

On the 30 August, after the rude 4.30am wakeup call, we set off on our bumpy 10 hour bus journey to Shivalaya, our first stop. The next few days along our route developed into a bit of a routine – we were woken up at 6am with “bed tea” and a bowl of warm water (parents take note please), and after packing up our duffle bags had a hearty porridge and eggs breakfast. These days involved up to 20km of trekking with undulating steep uphill and downhill staying at an average altitude of 2,500m for the first week. This was a massive challenge for us all despite our training, but our hill fitness did improve over the 3 weeks. The weather was typically hot and humid, peaking in the high 30 degrees at some points. It was great to finally reach the infamous Namche Bazaar, our campsite which was a 15 minute walk up from the shops offered a wicked view over the colourful buildings all nestled in the valley. All of our team were thankfully dealing with the altitude well so far, so we decided to push on to Thame and then to Thengpa at 4,300m on consecutive days and save our acclimatisation days for higher altitude.

Throughout our 3 week trek, our team were participants for a medical research project, investigating the effect of nitrate supplementation in the form of concentrated beetroot juice versus protein supplement on the symptoms of altitude sickness, fitness markers and inflammation of the bowel. This involved us doing twice daily assessment of blood pressure, oxygen saturation and Lake Louise scores for altitude sickness symptoms. In addition to this there was a step test every few days, plus stool samples (!) where we looked at the level of Calprotectin – a market of bowel inflammation. I was randomly selected into the concentrated beetroot juice group, which was a daily struggle! I’m really excited to see the results, as I’m so interested in how the human body copes in extreme environments. It’s a core part of expedition medicine and applicable to occupational medicine in the Royal Air Force, where pilots and deployed personnel can be subjected to hypoxia in daily life and training.

As time went on, our sights were set on our ultimate expedition goal: conquering the Tesi Lapcha Pass at 5,255m. We spent a few hours at most trekking during the day, where we generally leap-frogged our campsite to gain higher altitude in order to maximise acclimatisation, have a snickers at the top and then come back down to base for a carb-filled lunch.

The environment had shifted away from the lush humid forests we had been in before, and now barren landscapes of moraine and scree slopes were in the shadow of snowy peaks. The atmosphere first thing in the morning was dramatic with great clouds of mist creeping up the valley, and at night we could have been in a National Geographic magazine with our tiny little tents beneath the great expanse of the milky way.

After much logistical organisation between teams and advice from the Sherpas on how to tackle the extreme conditions of the pass, our plan had been decided: early morning on the 15th September, we would take on the Tesi! We woke up at 2.45am to have a quick bowl of steaming porridge and set-off by 3.30am with our head torches into the darkness. Our plan was to reach the top of the pass as soon as we could after sun-rise in order to minimise our exposure to rock-fall, which would start to happen when the ice began melting. What followed was about 4 hours of tackling a challenging rocky slope, followed by a scree slope which was on top of the glacier. When the sun rose it gave us some of the best and most unique views of the expedition, it’s what makes mountaineering worth it! When we reached the top of the scree, there was only 200m altitude left to gain, but the most dangerous part had begun as we were getting close to the areas of rockfall. With our helmets on we traversed around and up the side of the rock with confidence ropes in place to help us. This was one of the most physically challenging things I have ever had to do, while gasping for breath due to the lack of oxygen, the porters were shouting at us to keep going in order to get to safety. It was stressful to say the least but we all managed to do it! The last 100m or so we walked up in the first snow of the expedition and reached our highest point, 5,755m with huge smiles on our faces and amazing views – absolutely epic!

However, it was what followed that was definitely the most mentally challenging, as the worst part was not over yet…just 48 hours of moraine to go, where we had to abseil down portions and every step had potential to break your ankle – the lake we could see in the distance just wasn’t getting bigger! This part of the expedition truly demonstrated the importance of positive thinking and team work, and highlighted our team’s incredible ability to just keep plodding. On our last day, when the moraine had finally subsided, we were back in greenery again and our team’s morale magically lifted as our world gained colour and we lost altitude.

When we arrived back to Kathmandu after a mad 13 hour bus journey on the pot-holed roads again, a hot shower and proper bed were absolute bliss. These 3 weeks with the RAF and in the Himalayas had been insane, with incredible ups and downs, but I could not have asked for a better team to have done it with. I have learnt so much about mountaineering, the human body and the logistics of organising an expedition before, during and after. I have definitely developed as a person through the many challenges I faced, it was an experience like no other, and truly saw the extent of human spirit and the importance of a positive attitude. I have my University Air Squadron to thank for this amazing opportunity, and would encourage everyone with an adventurous spirit to get involved!

In the future I hope to utilise the mountaineering qualifications I have gained to be involved in squadron expeditions and to gain further training in this field. The experience has definitely opened up the world for me and I already have plans in the pipeline to go trekking in other mountain ranges all over the world! Expedition medic is definitely at the top of the list for things I want to do when I grow up…

Conclusion

Having been involved with this expedition since its formulation in late 2016, it was a tremendous experience for me to see the teams perform in such a cohesive and competent manner. Crossing the Tesi Lapsa Pass (5755m) is no mean feat and certainly an adventurous triumph for all involved.

The expedition model did not allow for any member, not least the Cadets nor UAS Officer Cadets, to have a free ride. Each member of the team had a daily role from media and communications to assisting with medical research or in fact leading a particular days navigation. The ‘get up and go’ attitude of all members to participate and learn was refreshing and exceeded any expectation I may have had.

In respect of the UAS team this was a fairly ground breaking expedition in joining individuals from lots of different units. Selection was finalised a full 12 months before the expedition and was done so largely on personality and ability to work for each other rather than a set of hard skills which were taught throughout their training. This paid off during the expedition and their team work shone through.

For all of the them this was a huge achievement – expect to see some of them at future RAFMA meets or hopefully in years to come as future Junior Officers in their chosen field. For the RAF Air Cadets, this expedition was unprecedented. Never before have Air Cadets been involved in an RAF expedition. Exposure to mountaineering, through the provision of training, practical experience and time spent with seasoned mountaineers is not a regular experience for Air Cadets and they have been inspired. The unity of achieved within the RAF/RAFAC members in team 4 is a testament to all individuals involved. Crossing the Tesi Lapsa Pass (5755m) is no mean feat and certainly an adventurous triumph for all involved.

The UAS Officer Cadets and Air Cadets have, from their initial Summer and Winter training, grown in confidence, competence and technical ability. All of them will go onto become active members of the AT community. Whilst they were the youngest on this expedition, it will not be long before they will be instructing and leading their own expeditions in the future.